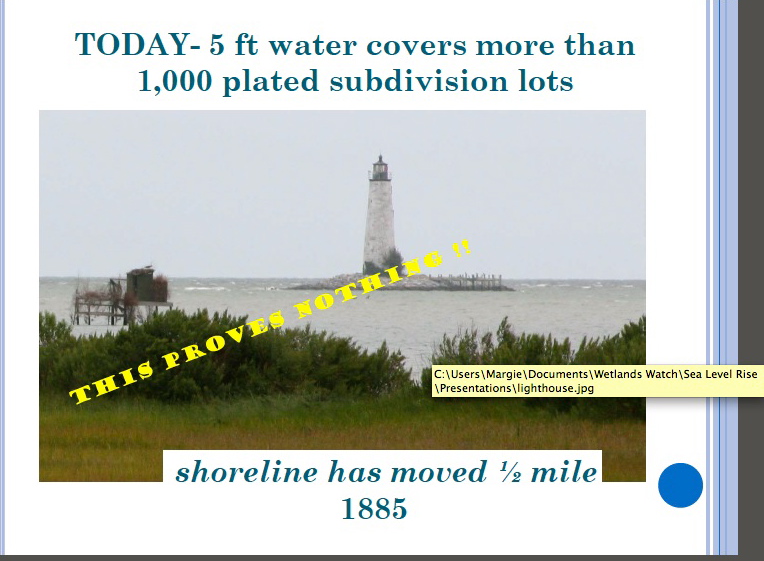

The last post showed this Wetlands Watch slide used in a Middle Peninsula Planning District Commission presentation.

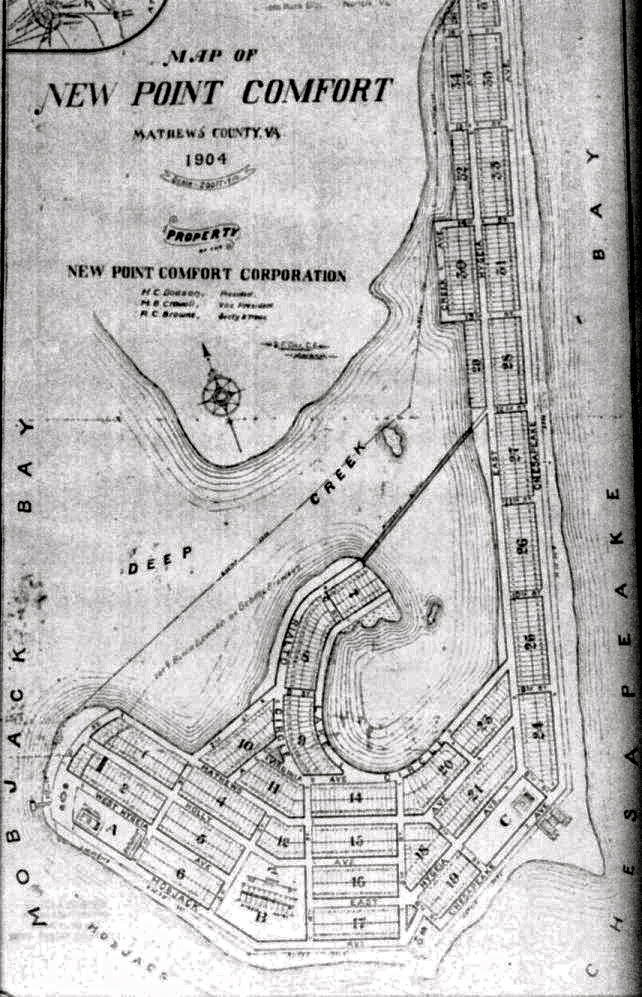

It’s true you’ll find water and some marshes today where the lots were shown on a 1904 Mathews County subdivision map near the lighthouse. But what the MPPDC/Wetlands Watch slide doesn’t say is the development company planned to fill in the tidal marshes and bring in sand to create beaches. The New Point Comfort Lighthouse site online says that the enormous cost to carry out that plan is what caused the company to go out of business the following year.

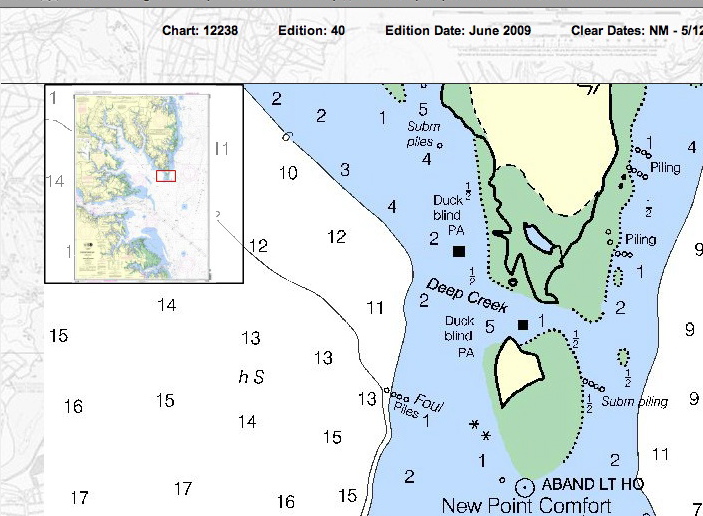

So what happened to the tidal marshes, sandbars and shoaled areas that existed in 1904 and earlier? And what about the photos and stories of people a generation or two ago who went to sandy beaches at New Point for picnics and outings?

Sand moves with the wind and waves. It is washed away, and bars and beaches reform at another place if there’s enough material available. But major storms can play havoc with that process. The Office of Naval Research describes one kind of current along the coast called the Longshore Current, how it moves, and how it can cause powerful and dangerous rip currents.

There’s an animation of the wave action that can produce sandbars on ONR’s educational Science and Technology Focus website at: http://www.onr.navy.mil/focus/ocean/motion/currents2.htm

With hurricanes and some other storms, the low pressure system increases the speed of longshore currents and height of waves. When these stronger longshore currents produce rip currents, they excavate channels through sandbars. The sand then accumulates in a quieter areas forming new bars. In this way, depending on the number and types of storms, and the intervals between storms, sandbars appear to migrate. When sand is exposed and dry, the wind then moves it to build up beaches–or blow them away. Beaches can only build up when dry sand is available. If the angle of a beach changes, so that the sand remains wet, the beach will not grow and can be diminished by wave action or the effects of storms.

The Chesapeake – Potomac Hurricane of August 23rd, 1933 and the one that hit on September 16th, 1933 ripped through the area around New Point Comfort, leaving two separate islands we see today. But the New Point Comfort Lighthouse withstood the tremendous winds and rain and waves, and isn’t that the story that really matters?