By Carol J. Bova

After the septic system of the former Seabreeze Restaurant failed in June 2016, the Board of Supervisors voted to postpone signing a new lease with the Hole in the Wall Waterfront Grill until repairs on the failed 1998 system were completed. Former county officials and the local health department influenced the Board of Supervisors to sign the lease in December 2016, but the septic repairs were not completed until a year later.

After the septic system of the former Seabreeze Restaurant failed in June 2016, the Board of Supervisors voted to postpone signing a new lease with the Hole in the Wall Waterfront Grill until repairs on the failed 1998 system were completed. Former county officials and the local health department influenced the Board of Supervisors to sign the lease in December 2016, but the septic repairs were not completed until a year later.

The county owns the .927-acre parcel which has a public boat ramp in addition to the restaurant. At less than one acre, it is too small to subdivide. Twice in 2017, in 2019, and again last year, the issue of selling surplus land, including this site, was raised and died in Board of Supervisors meetings. If the land were sold, there would be no way to guarantee the boat ramp would remain public.

As of March this year, the County has paid over $127,000 in septic pump and haul bills for Hole in the Wall Waterfront Grill. Many now recognize the Board should never have agreed to the lease until the septic system issues were resolved. Board minutes and FOIA requests eventually filled in the backstory of how former Mathews County Administrator, Mindy Conner, and former Building Official, Jamie Wilks misled the Board.

This was not the first time Conner acted against the County’s best interest. Conner and two other former county employees are involved in a lawsuit filed by Mark Eubank that went all the way to the Virginia Supreme Court. The details were in “A Malicious Prosecution” published in Bacon’s Rebellion in September 2021. The case was sent back to the lower court and is scheduled to be heard later this year.

On September 27, 2016, Wilks told the Board that the issues with the restaurant’s septic system were in the process of being resolved, and repairs would begin after an inspection in the coming week. Although the lease was still being negotiated, Wilks reported he had already given Mac Casale a permit to begin interior demolition of the former Seabreeze Restaurant. The Board voted to delay signing the lease until the septic repairs were complete.

On October 25, Wilks told the board he had received a preliminary report from the septic contractor, soil scientist and septic engineer, and he had to work with the Health Department on their recommendations. He said the Health Department already told him they would approve the repairs, and the process was “just the technicalities.” He did not inform the board that the scientists had no viable solution to return the system to normal function.

At the November board meeting, Conner said, “We have a path to getting the approval…an agreement on the scope of work they want us to do.” She urged the supervisors to go ahead and authorize her to execute the lease on their behalf because it wouldn’t take effect until the Health Department approved the septic system for use. The board gave her the authorization, and the lease was signed on December 1.

The supervisors were still not told the October inspection by the septic system experts showed the septic system was discharging into the groundwater which was at the depth of the drainfield chambers. (The drainfield is under the parking lot.) There is also no record that the board knew the local health department representative, Patricia Duttry, had written an email to Conner and Wilks on November 7 saying “Because of the shallow seasonal water table and depth of the drainlines, the design would have to meet the Regulations for Alternative Onsite Systems related to direct disposal to ground water.” She offered to support a variance from the required treatment levels which could only be granted by the State Health Commissioner.

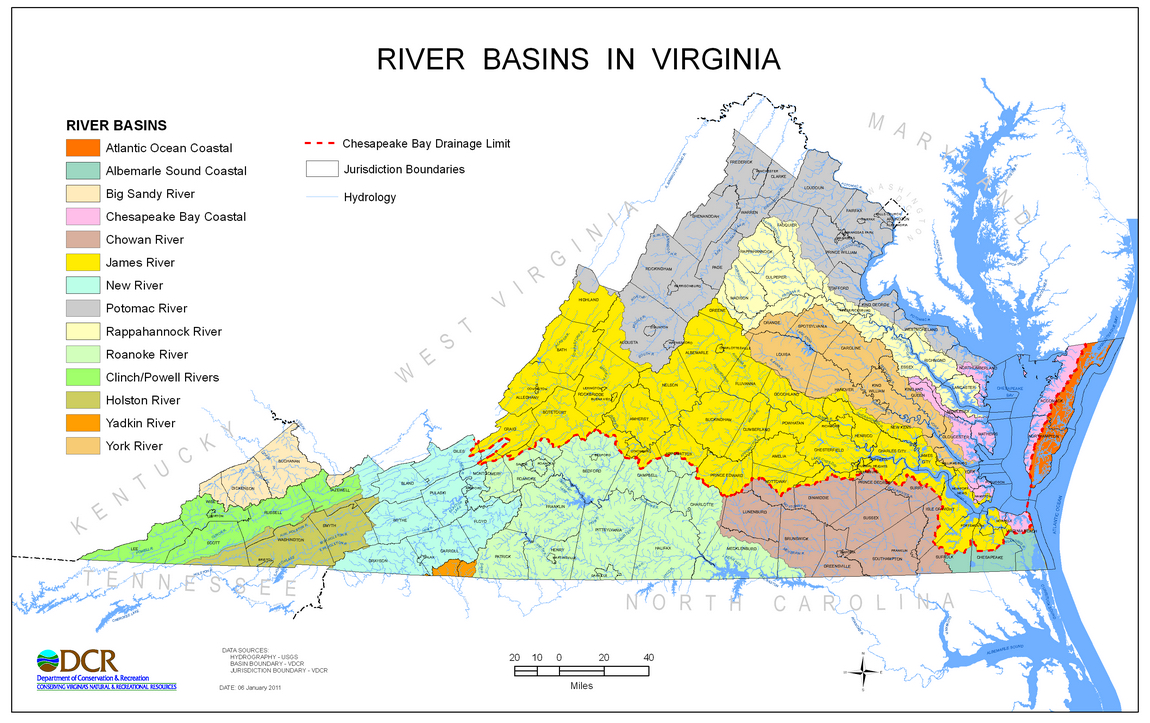

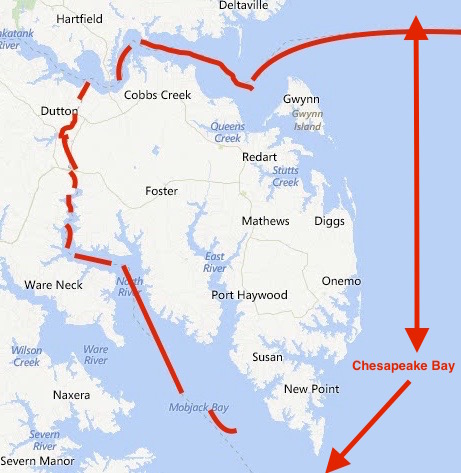

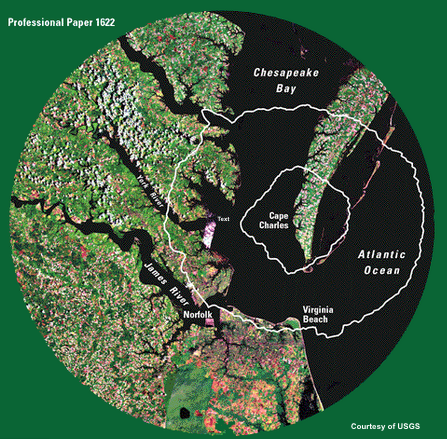

It is a mystery why Duttry would go along with direct discharge at a waterfront location at Milford Haven which connects to the Chesapeake Bay instead of saying she would have to pull the septic system operating permit if the county could not meet the health department’s septic system standards.

On December 5, 2016, Wilks confirmed to Duttry the septic system drainlines were not damaged or blocked and asked to begin repairs immediately. He added, “We would include the missing items that were never installed.” In spite of FOIA requests, the last line of this email has never been explained: What items for the septic system had been missing from the original 1998 installation?

On December 7, Duttry told Conner and Wilks they could still use the 1998 septic permit “for 45 seats/380 gallons per day (and using a 1000 gallon Multi-flo unit for treatment to reduce biological oxygen demand and total suspended solids) so there would be no room for expansion.”

The septic contractor wrote to Conner and Wilks on January 7, 2017 and included the findings and recommendations from the October inspections and testing. The soil scientist’s report said, “The three drainlines are completely in the water table. It is amazing it has worked as long as it has….I really have no viable solution for repair.” He then discussed creating an elevated mound which would eliminate the parking lot, or consider trying to obtain a permit for direct discharge into the ground water. (Note that Duttry was already aware of this recommendation the previous month.) The soil scientist also said, “Maybe the permanent pump and haul is the best option, but this will be costly, especially during peak season.” He noted, “Health Department Regulations generally prohibit permanent pump & haul.”

This information was not shared with the supervisors, and Conner hired two companies to do work on the system, then chose one to complete all the repairs. The company submitted a report to the health department at the end of December 2017 that with the maintenance and repairs that were done, the system should return to normal function. It turned out that even more work was needed, and again in May 2018, a second report to the Health Department repeated that the system was functioning as designed.

As part of the lease, the tenant was to raise the building out of the floodplain.

HITW raised off the ground

The restaurant opened in July 2019, but a year later, Duttry told the Mathews Gloucester Gazette Journal about more problems. “The high water table is one of those problems, she said, but the issue that has been causing eruptions of effluent onto the ground has to do with the aeration and filtration systems in the engineered septic system. There seems to be an excessive buildup of fats, oils and greases in the aeration tanks, she said, and thus far no one has been able to pinpoint the cause.”

Imagine that. A buildup of fats, oils and greases in a restaurant septic system, and no one could pinpoint the cause.

Because of the sewage eruptions through potholes in the parking lot, the county arranged for pump and haul of the waste beginning in July 2019.

Casale worked with former county administrator Mindy Conner to solicit a proposal for an ozone disinfection system from NextGen Septic Solutions in Ohio to be used with the existing Multi-Flo septic system. In November 2019, Casale corresponded with Pat Duttry and David Fridley from the Virginia Health Department (VDH) on how to get approval to install the system which was not approved for use in Virginia. He was told to arrange a preliminary engineering conference to review the proposal and that final plans would need to be prepared by a Professional Engineer licensed in Virginia. A copy of the VDH reply was sent to Conner.

Almost a year later, on September 1, 2020, NextGen sent Conner their technical proposal. The Board of Supervisors wasn’t officially informed of the proposal until their September 22, 2020 meeting packet was distributed. Although the board voted “to authorize staff to move forward with the pilot program as offered by the Health Department,” the next day, Casale sent the proposal to VDH.

Ten months later, according to Board minutes, Conner told the Board on May 24, 2021, the permit fee was “between $200 and $250 for the Hole in the Wall septic repair. She noted that the proposed system would be a NextGen system.”

Four days later, May 28, 2021, without using public purchase policy and without a bid process, without a formal contract or board approval of the original invoice, Conner approved the first payment of $50,000. The invoice of $72,800 did not include shipping, site preparation, on-site installation, taxes and permit fees. The check dated July1, 2021 was voided and reissued on July 27, 2021 under the ARPA account as a capital outlay. There was no record posted to the board or public until the August 23, 2021 meeting packet.

On July 23, 2021, a week before she retired for medical reasons, Conner wrote, “Accepted by Melinda Conner 7/23/21” on a NextGen Scope of Work with no amounts shown.

On November 5, 2021, interim county administrator Sandy Wanner approved a second payment of $18,000.

The county received a third NextGen invoice dated January 28, 2022 to upgrade the system to 544 gallons per day at a cost of $128,900 with $60,900 still due, plus all the additional charges for shipping and installation.

It should be noted Duttry’s 2016 statement was that the VDH septic system permit did not allow for any expansion, and that the lease on page 8 said capital improvements were the responsibility of the tenant.

In regard to the last point, Casale provided NextGen an inaccurate sewage usage number of 384 gallons per day (gpd). (The street number is 384, 380 gpd is the permit amount.) The NextGen proposal addressed to Casale said, “It is assumed that all of the above treatment units are working, as designed.” But they were not, and the site was on pump and haul because of effluent eruptions onto the ground. The system was certified to the health department as functioning in May 2018 before the lease began on June 1, 2018.

No new design or engineering report was submitted to VDH showing the system could meet the current standards, not the 1998 standards the restaurant permit used. But even the proposed new upgraded system’s maximum capacity of 544 gallons a day will not resolve the problem because the restaurant water meter readings show they used more than that daily average for every day in both July and August 2022, and that does not consider melted ice and other discarded liquids.

The NextGen proposal states the air temperature requirements are 32 to 95 degrees F and the dryer unit for the ozone generator is used up to 75% relative humidity. This makes its use as an outdoor system questionable for Gwynn’s Island. The site cannot support a new drainfield that can handle the Hole in the Wall Grill’s volume of effluent, so that rules out a number of other options.

The pumping expenses are over $127,000 from July 2019 through March 8, 2023. The daily average of water meter readings generally ran between 500 and 833 gallons in the warm weather season from July 1, 2022 through September 19, 2022. Only two weeks showed an average per day at or below the permitted 380 gallons a day going to the septic system. (These averages include days when the restaurant was closed.)

Adding the pumping cost and the amounts paid to NextGen adds up to just over $195,000. Paid by taxpayers Now, the Board of Supervisors will hold a public hearing March 28 to see what taxpayers think about spending another $307,000 to correct the problems caused by the tenants’ raising of the building and improper foundation work that created a safety issue. (See Unsafe Structure Notice including lease and structural engineeer’s report here for details.)

If the County repairs the building, the total from taxpayers would be over half a million dollars. All because former county staff did not disclose facts that would have prevented the Board from going ahead with the lease, a tenant who would not abide by the VDH permit limitations, and the failure of the former building official to properly inspect the construction involved in raising the restaurant.

No other business in the county receives a subsidy from taxpayers for their business expenses. This one shouldn’t either.

Update: At the March 28 Board meeting, the county administrator provided a Powerpoint presentation with a timeline of events and the options, along with the budget impacts. Click here for that slide show.

The Washington Post published a

The Washington Post published a