After you read this summary, take a look at Gov. McDonnell’s Feb 7 press release: http://insidethecrater.com/?p=316

Virginia’s Oyster Harvests Boom

– 2011 Harvest was the Best Since 1989; 2012 Harvest May be Largest in 25 Years – Over Past Decade Harvest Increases Ten-Fold: from 23,000 bushels in 2001 to 236,000 bushels in 2011; Dockside Value of Harvest Increased from $575,000 to $8.26 million

How would the USACE Oyster Restoration Master Plan really affect Virginia?

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

DRAFT

Chesapeake Bay Oyster Recovery:

Native Oyster Restoration Master Plan

March 2012

Forward

The State of Maryland and the Commonwealth of Virginia are the local sponsors for this study. As such, the native oyster restoration master plan (master plan) was prepared in close partnership with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) and the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the Potomac River Fisheries Commission (PRFC), and the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) are collaborating agencies for the project.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, helped shape the Chesapeake Bay and the people that have settled on its shores. The demise of the oyster in the 20th century culminated from a combination of overharvesting, loss of habitat, disease, and poor water quality. The problems faced by the oyster in the Chesapeake Bay are not uncommon along the Eastern Seaboard of the United States (Jackson et al. 2001; Beck et al. 2011). However, oyster restoration in the Chesapeake Bay has proven challenging. Past restoration efforts have been scattered throughout the Bay and have been too small in scale to make a system-wide impact (ORET 2009). Broodstocks and reef habitat are below levels that can support Bay-wide restoration, and critical aspects of oyster biology, such as larval transport, are only beginning to be understood. However, even in their current state, oysters remain an important resource to the ecosystem, the economy, and the culture of the Chesapeake Bay region that warrant further restoration efforts. Comprehensive oyster restoration is paramount to a restored Chesapeake Bay. This native oyster restoration master plan (master plan) presents the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ (USACE) plan for large-scale, concentrated oyster restoration throughout the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.

This master plan represents the culmination of a highly intensive, transparent, and exhaustive effort to bring together state-of-the-art science, on the ground experience, and collaborative planning focusing on native oyster restoration in the Chesapeake Bay into one comprehensive and coordinated document. This effort, which builds on USACE’s Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for Oyster Restoration Including Use of Native and/or Non-Native Oyster in 2009 (http://www.nao.usace.army.mil/OysterEIS/FINAL_PEIS/homepage.asp), is unprecedented in that it lays out the first comprehensive Bay-wide strategy for large-scale oyster restoration. Development of the document and the approaches laid out herein were accomplished painstakingly and with a thoroughness of purpose that this complex restoration challenge deserves. The authors and collaborators sought out the most up-to-date and credible sources of information to inform decision-making and plan formulation, including peer reviewed publications, and scientific and technical work accomplished by Bay experts, state partners, Federal collaborating agencies, non-government agencies, numerous stakeholders, and others with interest or expertise in native oyster restoration. Critical and controversial topics were isolated by the project team and analyzed through a series of Technical White Papers that were vetted among USACE, the project sponsors, and collaborating agencies. Intensive agency technical review of this document was accomplished by USACE with complementary reviews by other Federal and state partners to ensure technical quality and to address the full spectrum of technical and institutional concerns. Further public review of this document will complement the sound technical and institutional foundation on which this document has been built.

USACE, Baltimore and Norfolk Districts, have the authority under Section 704(b) of the Water Resources Development Act of 1986 (as amended by Section 505 of WRDA 1996, Section 342 of WRDA 2000, Section 113 of the FY02 Appropriations Act, Section 126 of the FY06 Appropriations Act, and Section 5021 of WRDA 2007) to construct oyster reef habitat in the Chesapeake Bay and have been designated as co-leads with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to achieve oyster restoration goals established by the Chesapeake Bay Protection and Restoration Executive Order (E.O. 13508) (May 15, 2009).

USACE restoration efforts have been ongoing in Maryland since 1995 and in Virginia since 2000. In recognition that a more coordinated Bay-wide approach is needed to guide USACE’s future Chesapeake Bay oyster restoration efforts and the investment of federal funding, USACE’s Baltimore and Norfolk Districts partnered with multiple agencies to create a joint Bay-wide master plan for oyster restoration efforts. Federal involvement is warranted due to the magnitude at which oyster populations have been lost in the Bay; the significant role oysters play in the ecological function of the Bay, as well as the socio-economics, culture, and history of the region; and the challenges confronting successful restoration. The purpose of this master plan is to provide a long-term strategy for USACE’s role in restoring large-scale native oyster populations in the Chesapeake Bay to achieve ecological success. It is conceivable that the master plan will serve as a foundation, along with plans developed by other federal agencies, to work towards achieving the oyster restoration goals established by the Chesapeake Bay Protection and Restoration Executive Order (E.O. 13508).

The master plan is a programmatic document that: (1) examines and evaluates the problems and opportunities related to oyster restoration; (2) formulates plans to restore sustainable oyster populations throughout the Chesapeake Bay; and (3) recommends plans for implementing large-scale Bay-wide restoration. The document does not identify specifically implementable projects.

The long-term goal or vision of the master plan is as follows:

Throughout the Chesapeake Bay, restore an abundant, self-sustaining oyster population that performs important ecological functions such as providing reef community habitat, nutrient cycling, spatial connectivity, and water filtration, among others, and contributes to an oyster fishery.

USACE recognizes that self-sustainability is a lofty goal. It will require focused and dedicated funding and strong political and public support over an extended period, likely decades. It will require the use of sanctuaries and the observance of sanctuary regulations. In addition to the long-term goal, the master plan defines near-term ecological restoration and fisheries management objectives. The ecological restoration objectives cover habitat for oysters and the reef community as well as ecosystem services.

The master plan lays out a large-scale approach to oyster restoration on a tributary basis and proposes that 20 percent to 40 percent of historic habitat (equivalent to 8 percent to 16 percent of Yates/Baylor Grounds) be restored and protected as oyster sanctuary. The concentrated restoration efforts are necessary to have an impact on depleted oyster populations within a tributary. To accomplish tributary-level restoration, the master plan includes salinity-based strategies to address disease and jumpstart reproduction.

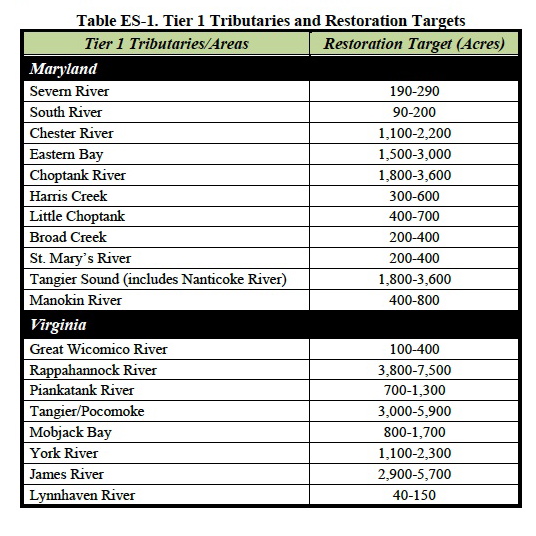

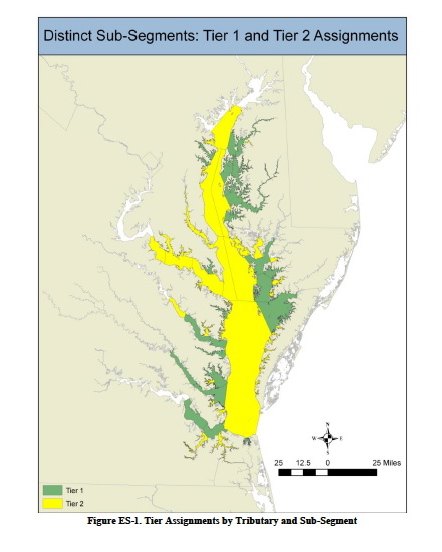

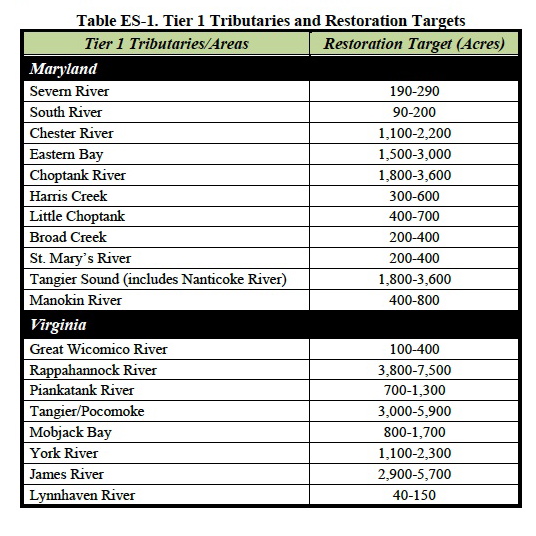

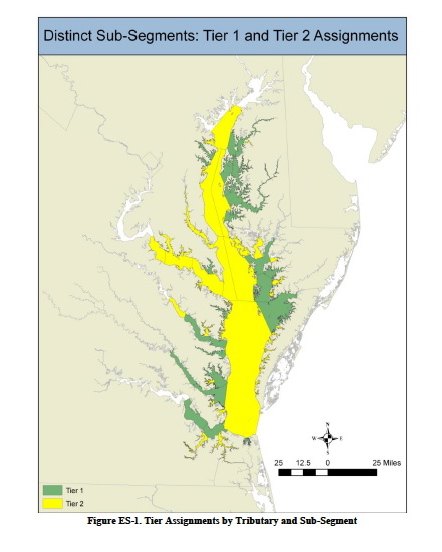

USACE and its partners evaluated 63 tributaries and sub-regions for their potential to support large-scale oyster restoration using salinity, dissolved oxygen, water depth, and hydrodynamic criteria. Salinity largely controls disease, predation, and many other aspects of the oyster life cycle and by its consideration, the master plan indirectly addresses these other factors. The evaluation was largely performed using geographic information system (GIS) analyses. The master plan identifies that 19 (Tier 1) tributaries in the Chesapeake Bay are currently suitable for large-scale oyster restoration (Table ES-1). These tributaries are distributed throughout the Bay with 11 sites in Maryland and eight sites in Virginia, as shown in Figure ES-1. Tier 1 tributaries are the highest priority tributaries that demonstrate the historical, physical, and biological attributes necessary to provide the highest potential to develop self-sustaining populations of oysters. The remainder of the tributaries and mainstem Bay segments are classified as Tier 2 tributaries, or those tributaries that have identified physical or biological constraints that either restrict the scale of the project required or affect its predicted long-term sustainability. The master plan also discusses additional criteria that should be investigated during the development of specific tributary plans such as mapping of current bottom substrate, sedimentation rates, and larval transport and provides a framework for developing specific tributary plans.

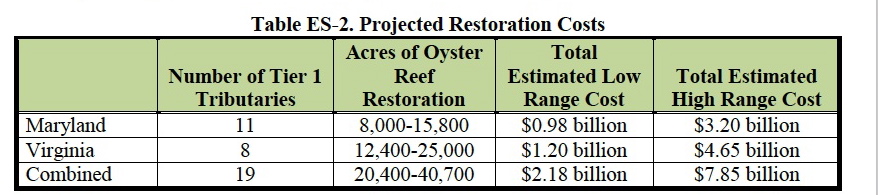

The restoration targets provided in Table ES-1 are estimates of the number of functioning acres of oyster habitat needed within a tributary to affect a system-wide change and ultimately provide for a self-sustaining population. The targets are not meant to be interpreted strictly as the number of new acres to construct. Any existing functioning habitat identified by bottom surveys would count towards achieving the restoration goal, but would not be counted toward new restoration benefits. Similarly, there may be acreage identified that only requires some rehabilitation or enhancement. Work done on that acreage would also count toward achieving the restoration target. The accounting of the presence and condition of existing habitat is recommended as an initial step when developing specific tributary plans. Once that information is obtained, restoration actions will be tailored to the habitat conditions and projected restoration costs (Table ES-2) revised.

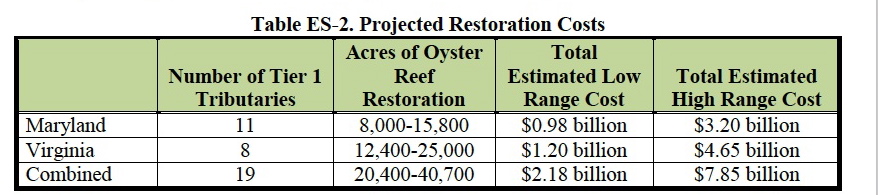

The master plan includes planning level restoration costs that incorporate construction of high relief (12 inches) hard reef habitat (using shell and/or alternate substrates), seeding with spat (baby oysters), and adaptive management actions. Estimates are provided for the full construction of the low and high restoration targets. The summary of these costs for all Tier 1 tributaries is provided in Table ES-2. Estimates are conservatively high in that the assumption was made to develop the cost estimates that each acre would require construction of new hard habitat; however, it is anticipated that restoration will not require new habitat construction for every targeted acre. Although Table ES-2 concisely shows the costs for restoring all Tier 1 tributaries, one should not assume that all tributaries need to be restored before benefits are achieved. Further, USACE is not recommending an investment of this magnitude at any one time. Restoration should progress tributary by tributary. Benefits are achieved with each reef and each tributary that is restored. The master plan provides a further breakdown of costs by tributary and separate costs for substrate placement and seeding.

The ecosystem services provided by oysters are numerous (Grabowski and Peterson 2007), but largely difficult to quantify at this stage of restoration. These services include:

(1) production of oysters,

(2) water filtration, removal of nitrogen and phosphorus, and concentration of biodeposits (water quality benefits),

(3) provision of habitat for epibenthic fishes (and other vertebrates and invertebrates),

(4) sequestration of carbon ,

(5) augmentation of fishery resources,

(6) stabilization of benthic or intertidal habitat (e.g. marsh), and

(7) increase in landscape diversity.

Given the vast resources required to complete restoration in all Tier 1 tributaries and the fact that large-scale restoration techniques are in the early stages of development, USACE recommends choosing a tributary or two in each state for initial large-scale restoration efforts following completion of the master plan. This would facilitate the concentration of resources to enact a system-wide change on oyster populations in the tributary and achieve restoration goals, as well as provide for monitoring and refinement of restoration techniques. Monitoring will be guided by the report of the multi-agency Oyster Metrics Workgroup convened by the Sustainable Fisheries Goal Implementation Team of the Chesapeake Bay Program (OMW 2011).

Implementation of large-scale oyster restoration should begin with the selection of Tier 1 tributary(ies) for restoration by restoration partners. Specific tributary plans should be developed for the chosen tributary(ies) and should include a refinement of the restoration target, originally developed in the master plan. (NOAA has initiated development of a draft Tributary Plan Framework that is attached to the master plan in Appendix D.) Restoration partners should work together to acquire and evaluate mapping of current bottom substrates to initiate plan development and scale refinement. The master plan describes many other implementation factors that need to be considered during tributary plan development. Appropriate National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) documentation would accompany each tributary plan. Once a tributary plan is complete, construction would proceed in a selected tributary by restoring a portion of the target (e.g., 25, 50, or 100 acres) per year given available resources until goals and objectives are met.

The master plan is proposing a sanctuary approach to fulfill USACE’s ecosystem restoration mission and the E.O. goals. In developing the master plan, USACE views oysters as “an ecosystem engineer that should be managed as a provider of a multitude of goods and services” (Grabowski and Peterson 2007). The recommendation for large-scale restoration in sanctuaries has been developed to concentrate resources, provide for a critical mass of oysters and habitat, and promote the development of disease resistance; this strategy is expected to be a significant improvement over past restoration efforts. Establishment of long-term, permanent sanctuaries is consistent with recommendations of the Chesapeake Research Council (CRC 1999), the Virginia Blue Ribbon Oyster Panel (Virginia Blue Ribbon Oyster Panel 2007), and the Maryland Oyster Advisory Commission (OAC 2008). Sanctuaries are necessary to enable the long-term growth of oysters, develop the associated benefits that increase with size, and develop disease resistance. Carnegie and Burreson (2011) also have proposed that sanctuaries may be a mechanism by which to slow shell loss rates.

Although limited, current information suggests that greater economic and ecological benefits are achieved through the use of sanctuaries (Grabowski and Peterson 2007; Santopietro 2008; USACE 2003, 2005). USACE is undertaking additional investigations into the costs and benefits of sanctuaries and harvest reserves. Future tributary plan development which will include applicable NEPA analyses and documentation will incorporate the findings of these investigations. Inclusion of management approaches other than sanctuaries will be considered in specific tributary plans, if justified. On the basis of current science and policy, USACE does support the efforts of others in establishing harvest reserves within proximity of sanctuaries to provide near-term support to the seafood industry and establish a diverse network of oyster resources.

There are a number of issues that may jeopardize the success of any large-scale oyster restoration program. Illegal harvests pose a major risk. Illegal harvests are suspected to have impacted nearly all past Maryland restoration projects as well as the Great Wicomico restoration efforts. Recent estimates are that 33 percent of oysters placed in Maryland sanctuaries between 2008 and 2010 have been removed by illegal harvests; a potentially greater percentage have been illegally harvested since the beginning of restoration efforts in 1994 (Davis 2011). Significant investments are lost and project benefits compromised when reef habitat is impacted by illegal harvests. The expansion of designated sanctuaries in Maryland and enforcement efforts by both Maryland and Virginia should help with reducing illegal harvests.

A second critical factor is the availability of hard substrate for reef construction. Oyster reef is the principal hard habitat in the Bay and significant amounts of reef habitat will need to be restored to meet restoration goals. However, a sufficient supply of oyster shell is currently not available for oyster restoration. Alternate substrates will need to be a part of large-scale habitat restoration. Alternate substrates such as concrete and stone are significantly more expensive and may not be publicly acceptable on such a large-scale; however, these materials greatly eliminate the risk of poaching because the materials can damage traditional harvest equipment. A third issue impacting the success of large-scale oyster restoration is water quality. A restored oyster population has the potential to return filtering functionality to shallow water habitat in the Bay. However, poor land management and further degradation of water quality will jeopardize any gains. Ultimately, water quality benefits provided by oyster restoration will rely on sustainable land management and development. Efforts being undertaken to support the Chesapeake Bay Restoration and Protection Executive Order and the nutrient reduction goals established in the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDL) will help address water quality issues. The Executive Order goals targeting water quality, habitat, and fish and wildlife are directly related to achieving the goals presented in the master plan. Opportunities to match oyster restoration efforts, spatially and temporally, with land management projects should be implemented to the greatest extent.

Although USACE and its partners have developed this master plan to guide USACE’s long-term oyster restoration activities, large-scale oyster restoration in the Chesapeake Bay will only succeed with the cooperation of all agencies and organizations involved. VMRC and USACE-Norfolk are working together towards some common ground activities including oyster benefits modeling, a fossil shell survey, monitoring, and rehabilitation of existing sanctuary reefs; and these efforts should continue in the future. Resources and skills must be leveraged to achieve the most from restoration dollars. The greatest achievements will be made by joining the capabilities of each agency in a collaborative manner to pursue restoration activities.

Link to the full report:

Click to access CB_OysterMasterPlan_March2012_LOW-RES.pdf