Sometimes, facts don’t matter when feelings are involved. At this point, I don’t expect any information will make a difference to those opposed to the Milford Haven oyster aquaculture project, but perhaps folks who are less intensely involved will be interested in a few more facts.

The essence of the conflict that’s led owners from the Gwynn’s Island Condominiums and a few others to wage an intense campaign of objections are the three perceived personal impacts of the project: the impact on their view, a potential reduction in property values and some negative effect on their quality of life.

The exact number of households involved in the protests to the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC) is unknown because addresses are not required with comments. Some husbands and wives filed separate protests saying the same things, and a few filed duplicates. One couple filed five protests between them. This is an indication of how distressed these individuals feel about the project.

The 83 couples or individuals who filed 98 protests with 295 objections. Of those, 221 were based on misinformation, lack of information, or incorrect assumptions about the nature of the project and how VMRC permit applications are reviewed. (A quick review: If the project is approved, there will be no new processing, tumbling or pressure washing, so no new noise. No odors, no large trucks. Water access won’t be blocked and navigation will not be impacted. The only environmental impacts will be improvement in water clarity, filtering of algae and sediment. No eelgrass beds are under the proposed area.)

The remaining 74 statements are the personal ones.

Quality of life is subjective, and if the incorrect assumptions are set aside, there are no details to explain how the protestors would be affected.

To support claims of how the change in the view would affect negatively affect their lives, the protesters used photographs found online to show what they called “floating coffins.” These photos did not show the same cages proposed for the Milford Haven project or show what the view might be from the shore to the proposed site.

This detail of the photo above shows what appear to be wood slats. There is nothing on the planned cages like this.

This is a view of the actual type of 3′ x 4′ x 1′ cage with two prism shaped floats, 3 ft x 9 inches wide x 1 ft high. Note the size from only 20 feet away. There are no residences within 500 feet of the planned site. See close up below.

Rezoning Issue

Having cages on the dock was another impact on view that the protesters cited. Ironically, the protesters have lobbied against a Mathews County zoning change that would allow Island Seafood to put a storage building on an adjacent vacant lot they own to the north. It would require a change from R-2 to B-1 as a complement to the existing business. The company would retain a wooded buffer from other properties, which are also vacant at present. The irony is in the fact if the lot cannot be rezoned to allow cage storage, they will be stored on the dock. [Note: Corrected current zoning to R-2. Picked R-1 up in error from the newspaper account.]

Property Values

One protest included a statement from a real estate professional saying a study found property values would be reduced was neither a study nor about aquaculture.

I am sure that you are aware of the study that has been done in Surry County. According to the findings, some of the properties have seen their values drop as much as 30%, as much of the value of waterfront property is tied to its view!” (VMRC Protest #21.)

There are no records of any such study in Virginia, however, a broader search found the origin of this story. It was not in Virginia, and there were no findings from a study. The situation involved one property in the Town of Surry, Maine. A homeowner requested a 30% reduction in his real estate tax assessment based on truck traffic and long term parking at a waterfront restaurant and dock across the road from his home. From the one local news report available online, the selectmen did not challenge the request, but granted it. In the same article, other residents said there was no need for such a large reduction.

Two years later, this reduction was used to object to an aquaculture project in Maine by the same selectman who granted it. The Department of Marine Resources in Maine rejected this objection, as well as others that cited interference with contemplative, spiritual and meditative values of the area since “that would introduce a subjective element into the lease process that would be inconsistent with the statutory scheme and impossible to administer.”

Obstruction or Change?

How much will a field of 17 rows of objects one foot high or less, placed 25 feet apart obstruct a view? It depends how close the viewer is, doesn’t it? At water level, say turtle’s-eye view, there’ll be some obstruction, but from the land, there is none. The condominium, private residence and commercial piers are more than one foot above the water, and they do not obstruct the view.

The view above is from a drone flying a few feet above the boat in the picture. Jet skis, kayaks, sailboats, fishing boats, all have a higher profile than the planned aquaculture cages. And the condos and homes are at a level higher than that the drone used. So it’s not the obstruction, it’s the change in the view that is being challenged.

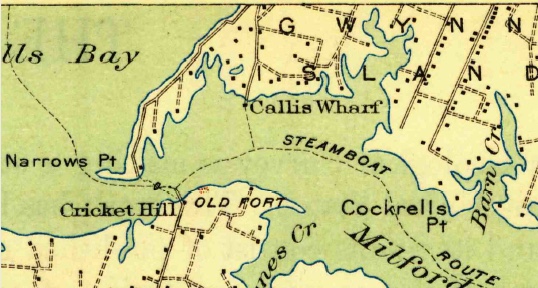

Like it or not, the historic use of this area is for commercial waterfront, not condominiums and vacation homes. There were 13 waterfront residences from Narrows Point to Edwards Creek in 1917. They all saw the steamboats that sailed around the Narrows to Callis Wharf, Cricket Hill Wharf and Fitchett’s Wharf until the 1930’s. They didn’t object to that or to the many smaller craft bringing produce, fish and oysters and other goods to and from the wharf.

Will one-foot high floats on a small part of the entire area really interfere with anyone’s view? Or is it that a select group feel they should have exclusive use and control over all they see and stop a project that will bring jobs, new tax revenue, and better water quality for Milford Haven?